Warrior Nation

The Historical Roots of American Violence

by Howard Smead

“You must understand that Americans are a Warrior Nation.”

— Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan

A pastoral America of strong, resolute, and honorable people steeped in Christian values and democratic ideals … Centuries of violence in the pursuit of honor, conquest, revenge, glory, and material gain. Mob actions, mass murder, lawlessness, and war.

We cherish one America, overlook the other. Then every so often wonder where all the violence is coming from.

For all its well-deserved exceptionalism—and it is well-deserved—America is also an exceptionally violent country with an exceptionally violent history. The Americas were violent before the Europeans arrived, and got even more so once they did. The settlers fought and conquered the native inhabitants, they fought other nationals for dominance, and they fought among themselves for preeminence. In what became the United States, murder and mayhem date back to desperate colonists clinging to life on the edge of a vast and, in their view, untamed wilderness. The struggle for survival and the competition for empire led to conquest and genocide. Ethnic and religious rivalry created rioting, rebellion, and repression in the form vigilantism and lynching. The 20th century brought serial killers, mass murder, and heavily armed hate groups threatening civil war. And all that sits on top of slavery, segregation, marginalization, and continued repression. All these and more have made America singular among western nations.[1]

And we ask plaintively why such violence?

In his sweeping history of American crime, Lawrence Friedman puzzled over this question, “Why is the United States such a violent country? Why is there so much serious crime? … Is American history, tradition and experience to blame?”

The answer to this question lies in a rather remarkable combination of ideas, events, attitudes, and conditions that make up our history. It lies in the nature of the country—in the different creeds and conditions that set America apart from other countries. It lies in many of the ideas and traditions flowing from them that constitute the basis of our exceptionalism. The causes are complex and changing. And it is extremely risky to blame American violence on any one factor. The bottom line is this: America is not now nor has it ever been an assemblage of “peaceable kingdoms.”[2]

Violent Exceptionalism

“... cannons were brought into play, and a pitched battle developed on Orleans street, near the Belair Market, between the Eighth Ward Democrats … and the Sixth and Seventh Ward Know-Nothings. At first driven back, but not to be outdone, the Know-Nothings brought forward and unlimbered a small swivel [gun], and the battle raged …it was astonishing how many boys were engaged in the fighting, and how many of these were shot while looking on.”

—Eyewitness account of 1856 election in Baltimore, Maryland[3]

Writer James Truslow Adams, who coined the term the “American Dream,” considered violence to be “one of the most distinctive American traits.”[4] And he had a mountain of facts on his side. “… American life has always been characterized by violent conflict,” says sociologist Joseph S. Himes, “virtually every sector and group in the nation has been caught up in violence at some time.”[5] Our greatest president, Abraham Lincoln, himself the very personification of the exceptional, remarked as early as 1837 that a profound threat to the “proud fabric of freedom” was “the caprice of the mob … which pervaded the country, from New England to Louisiana.” He predicted dire consequences if Americans didn’t stop leaving “dead men … literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every road side.”[6]

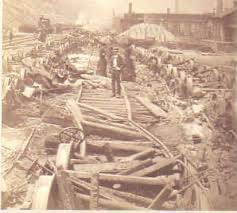

Violence started at Plymouth Rock and never let up, changing only in target and method. It was especially nasty during that holiest of holies the American Revolution. Conventional wisdom still clings to the myth of the Revolution as “a polite conflict led by gentlemen who could sully neither their reputations nor their silk clothes with atrocities.” In fact, the Revolution was a civil war in many quarters. Neighbors turned on neighbors, families fought families, patriot mobs seized tory property and executed the owners. “Patriots … did not tolerate doubters in their midst. Either you are for us or against us, they insisted.” Patriot committees forced enlistment, and imprisoned, banished, and tortured those who refused, or seized or destroyed their property. “Often local vigilantes preempted the committees by hounding those in their midst…”[7] As Richard Maxwell Brown described it, “the meanest and most squalid sort of violence was from the very beginning to the very end put to the service of revolutionary ideals and objectives.” This after almost 200 years of slaughtering (and being slaughtered by) Indians. The American Revolution sanctified violence and its implicit logic that the end justifies the means, and it has stayed with us ever since.[8]

This remarkable passage from Richard Maxwell Brown’s seminal work, Strain of Violence helps set the stage for what he calls the “violence of the ‘complex present’ of American life today.

The era of the American Revolution was marked by a series of outbreaks in town and countryside. Urban violence runs from the Stamp Act riots in 1765 through the Sons of Liberty violence, the Boston Massacre, the burning of the Gaspee, and the Boston Tea Party to the incident that triggered the Revolutionary War—the fighting at Lexington and Concord. Concomitant with that the urban violence of the 1760’s and 1770’s were the outbursts of violence in rural America: the Paxton Boys’ uprising in Pennsylvania and the Regulator Movements in North and South Carolina, the emergence of the so-called “cracker” as a violent Southern prototype on the colonial frontier, the rise of lynch law in Virginia, and the bloody Indian wars. The 1760’s and 1770’s—as well as the 1670’s and 1680’s, the 1830’s through the 1850’s, the 1870’s through the 1890’s, and the 1960’s—have been among the peak periods of violence in American history."[9]

The Deep Roots of American Violence

A Guide to Mass Shootings in America

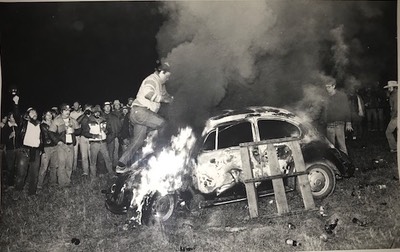

Fast forward through the nativist violence of the 19th century, the Civil War, the Age of Lynching, to “the 60s:” Riots by the dozens; assassinations; terrorism on the left; terrorism on the right; police riots; mass murder; serial killings; violent crime; cultural upheaval; a difficult-to-explain foreign war; a Cold War that sanctioned all manner of federal, state, and local privacy violations in the name of national security; and a defense policy that seemed to sum it all up: Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD)—all while the children of those defense strategists were being trained to duck and cover in response to a nuclear attack in hopes of delaying vaporization by a nanosecond or two.[10] The possibility scared the hell out of everyone, and sparked great cynicism, though a rosy view of the past persists.

The final report of the Kerner Commission study of American Civil Disorders concluded that “acts of collective violence by private citizens in the United States in the last 20 years have been extraordinarily numerous … in numbers of political assassinations, riots, politically relevant armed group attacks, and demonstrations, the United States since 1948 has been among the half dozen most tumultuous nations in the world.”[11] The irony of this somewhat breathless report was that America had experienced much greater civil strife. Nearly fifty years after the Kerner Commission Report, every time a spectacularly heartless mass shooting occurs, Americans are forced to think about themselves in a different light, at least for the subsequent twenty-four hours. Each new outrage seems to arrive via its own avenue of causation. After the May 2014 murder of seven people in Isla Vista, California, by a rejected twenty-two-year-old with a deep grudge against women and the men they choose, mainstream media raised tough questions about misogynist white men. [12] The massacre of twenty-six children and adults at Sandy Hook Elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut in December 2013 brought an anguished discussion of mental health issues and marginal parenting; the July 20, 2012 mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado, resulting in twelve dead movie-goers and seventy wounded implicated violent films and video games. An alienated, nativist white man killed six worshippers and wounded four others at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, on August 6, 2012—within a few months of one another. From the first mass slaughter in July 2012 to the last, May 2014, less than two years passed. Not too much before those incidents, a military psychiatrist with terrorist dreams killed thirteen military men and women at Fort Hood, Texas, on November 5, 2009, wounding thirty—discussions of politics, religion naturally followed. As did the pearl-clutching about race that occurred after the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012. Other factors are at play here, factors that when taken in combination offer the most cogent explanation for this apparent nightmare: Our history.

“…The past is never dead. It’s not even past”

—William Faulkner

Faulkner said this about the South, but I think it holds for the entire country. These days no one makes any pretense about the American people being genteel folk, even though the rosy view of the past persists. To an uncomfortable degree, America is a product of its bloody history. Whether it is the slaughter of fifty-eight at a country music festival in Las Vegas or twenty children and six adults in Newtown, Massachusetts, on December 14, 2012—both for unknown reasons— or the radical Islamist inspired slaughter of forty-nine in Orlando, FL, the spree-killing of thirty-two at Virginia Tech on April 16, 2007, or thirteen at Columbine High School in Colorado on April 20, 1999, or twenty-one shot dead at a McDonald’s in San Ysidro, California, on July 18, 1984, or a riot in South Central Los Angles from April 29 to May 4, 1992 leaving 60 dead, or over 200 riots during the “Long Hot Summers” of 1964, 1965, 1966, and 1967 and an additional 243 after the April 4, 1968, murder of Martin Luther King, Jr.,[13] or of the torture, rape and murder of eight Chicago student nurses on July 14, 1966.

These sad cases of mass murder are but the latest aspects of America’s violent culture. Mass murders have spiked over recent decades, but they should be seen in context as another phase of violent activity, public violence enhanced but not necessarily created by the availability of firearms with greater firepower.[14] Take just this one example from the past. On October 18, 1934, a Marianna, Florida, mob of several thousand tortured, mutilated—by excision of fingers and toes for souvenirs—castrated (and forced the victim to eat his severed genitalia), then dragged the man behind a truck and topped off the murderous spectacle by hanging the bullet-ridden corpse in the town square. The mob followed this up by roaming through the streets of the town attacking black people at random. When it was over, the local newspaper, which had advertised the impending lynching, complimented the crowd for its good behavior. This for a crime the victim did not commit.[15]

Perspective is important here. Through the 1960s the United States ranked about 14th out of eighty-four western nations in incidents of violence; hardly auspicious, though not bad overall, given our population size and geographic diversity. Another survey put the U.S. first in civil strife among western democracies but twenty-fourth among all nations.[16] We must always keep this in mind: the United States is not now and has never been “the most violent society that history has ever created,” as former terrorist Bernadine Dorhn once claimed. Not even close. Neither are the American people more depraved or barbaric than other peoples. They are not. They are neither the best behaved nor the worst. America is, as Richard Hofstadter put it, “a full-fledged and somewhat boisterous member of the fellowship of human frailty.” Governments, warlords, despots, and religious leaders of totalitarian nations of one stripe or another have rained death on their own people and others beyond their borders at grotesque proportions that dwarf anything the U.S. could ever be accused of. As Richard Slotkin writes, “There are no equivalents in American history of the programs of ethnic genocide carried out by the Turks against the Armenians or the Germans against the Jews; nor of the political genocide practiced by Stalin and Mao against opposition or dissident movements.”[17] So, my point is not that America is the most violent nation. My point is simply this: America is a violent nation with a violent history. Generations of violence heaped upon generations of violence have molded us into the nation and people we are today. The historical record and indeed popular culture do not remotely support any other assessment.[18]

Historical Amnesia

“We Americans are a peace-loving people. We seek friendship not only with our traditional allies but with our adversaries, too.

— President Ronald Reagan

“Americans who came of age during and after the 1930s found it easy to forget how violent a people their forebears had been,” and, as Hofstadter reminds us, historians have done little to remind them. For them, “conflicts between groups of citizens, no matter how murderous and destructive, have been forgettable.” No less a figure than Henry Adams thought Americans were “a people whose chief trait was antipathy to war, and to any system organized with military energy.”[19] While the history of American violence is well documented, until recent times it was largely absent from the history books. “What is most exceptional about the Americans,” Richard Hofstadter commented, perhaps with Adams in mind, “is not the voluminous record of their violence, but their extraordinary ability, in the face of that record, to persuade themselves that they are among the best-behaved and best-regulated of peoples.”[20] In 1968 the National Commission of the Causes and Prevention of Violence, defined this phenomenon as “historical amnesia.” One political scientist defined it as “the persistence of belief in the … aberrational quality of political violence.” Or, as Hofstadter explains, “a history but not a tradition of domestic violence.”[21] You’d have to wonder, though, if Hofstadter was overlooking such traditional values as popular sovereignty, the Code of the West, rugged individualism, and Manifest Destiny, all of which carry a least a subtext of violence.

When this amnesia combines with a national attention span measured in hours if not minutes, it makes for a naive view of the American past.[22] To this day an accurate understanding of the past eludes the public and is, in fact, being actively and often intentionally distorted, especially by right-wing media and dissident conservative political movements.[23] Hofstadter, who came late to the realization of our violent, conflict-ridden history, recognized the oddity of our lack of a cultural tradition of violence despite a history where violence was “frequent, voluminous, almost commonplace.”[24] This “non-tradition” was embedded well before the American Revolution. Historian Gordon Wood framed this in an interesting way. “Beginning with the Revolutionary movement (but with deep roots in American history) the people came to rely more and more on their ability to organize and to act ‘out-of-doors’ whether as ‘mobs,’ as political clubs, or as convention.” He labeled America’s long, pre-revolutionary history of mob violence “extra-legislative action.”[25] That’s putting it mildly. It was gruesome violence involving all manner of torture and humiliation. Given the Founders’ well-documented distrust of the middling sorts and the lower order that was behind some—but by no means all—of the bloody activities, they may well have responded to this assessment by questioning the difference among the three forms of outdoor activity.

The violence got worse during the actual Revolution, where barbarism by Patriots against Loyalists and British and mercenaries was ghastly. The casualty rate was higher than in all our wars except the Civil War;[26] the death rate among prisoners was the highest in all our wars. The relatively small numbers look insignificant, but they are a true indication of the level of this extremely violent and bloody revolution that in most quarters of the country was more of a civil war with the Patriots exacting a high price from British troops and officials and American Loyalists.[27]

The reasons for this collective memory loss may simply reflect a desire to forget unpleasant and painful events. But I think it underscores an important characteristic of American violence. Namely, that American violence has always lacked a unifying ideological or political core. Mob action and vigilantism did not share a common philosophical or political thread. They were about local issues. Violent acts weren’t communist, fascist, anarchist or monarchist, or even anti-monarchist, they were local and autonomous. Although there are pronounced racial and ethnic themes, rioters have come from all shades of the political spectrum. They have been white and Latino as well as black. They have been Protestant and Roman Catholic and secular. Similarly, violence has appeared in all parts of the nation. It lacks a geographical locus. Although the South has been the most violent region, owing to its connection to the inherently violent institution of slavery, lynchers, anti-labor thugs, and eye-gougers have cropped up in every quadrant of the map. Every time we try to puzzle out the latest act of wanton violence, a brief exercise this nation of intellectual lard butts doesn’t particularly enjoy, concern exhausts itself in a flurry of apocalyptic warnings and survivalist fantasies about societal collapse. Rest assured American society is not going to collapse, although too much mayhem might well stunt its growth. Why won’t it collapse? Here’s the monumental irony of it all: America is too violent to collapse.

Stability through Violence

“We are … heartily sick of this atmosphere redolent of insane violence … There is a strong party adverse to violent men and violent measures, but they are frightened into submission—afraid even to exchange opinions with others who think like them, lest they should be betrayed.”

—Joel Poinsett, southern political leader (1850)[28]

“Violence is as American as cherry pie.”

―H. Rap Brown (1967)

To Brown’s famous dictum, we might add, … and institutional stability as American as apple pie. This is the huge caveat that is crucial to understanding how why and how we are violent, and one of the enduring paradoxes of American history. Republican society stresses order, place, personal liberty, and equality, in that order. Violence, especially as some form of vigilantism, has often resulted when liberty and equality conflict. Lingering effects of these clashes surface from time to time in places as disparate as the Matthew Shepard lynching in Wyoming, or the Rodney King riots in South Central Los Angeles. Yet, no matter how one manipulates the statistics, whether ranking America high in domestic or foreign violence or higher than most nations, America comes out consistently as one of the most stable of all nations. As British writer G.K. Chesterton observed in 1922, “America is the only nation in the world that is founded on creed.”[29] Despite all the mayhem, only the far right disparages that creed. Natural rights and democracy in the context of a republican form of government have proven vastly preferable to monarchy, theocracy, oligarchy, communism, socialism, fascism, militarism, plutocracy, anarchy, or any other form of government that has been dreamt up. No, American violence is not about overthrowing the state; it’s about maintaining the state, or at least a certain view of it. The history of American violence is a history of a paradox: terrible violence and amazing stability. Our stability ranks easily with the most stable Western nations such as England and Scandinavia, while in terms of violence the U.S. looks more like a banana republic in the Western Hemisphere or an emerging Third World nation in the Eastern.[30]

The widely shared myth among Americans is that freedom means little or no government involvement in our lives, that we would still be living in a Jeffersonian nation of small towns, family farms, and sturdy yeomanry if only the government would get off our backs. And the only recourse we have against government is the nullification of state authority. We cling to this misconception like we cling to our guns and religion. In fact, the myth is inseparable from guns and religion as agents of that nullification. But, “…it is the state and the rule of law than make modern life possible. Its absence—not its presence— ‘creates conditions for new cycles of horrific violence.’” [31] In America violence has been used to protect “the American, the southern, the white Protestant, or simply the established middle-class way of life and morals.” [32] In other words, violence, especially collective violence—lynching, riots, vigilantism and the like, upholds tradition. It’s only when such repressive violence becomes untenable does society turn against it.[33]

Oddly, Americans overall have not directed their violent ways against their government. They raise bloody hell, but with the one glaring exception they don't rebel against their country. Political, economic, and cultural stability have proven enduring. And here’s the killer: violence has been the key to this. Quite the opposite of what you would think—that violence of any sort would be destructive and destabilizing—American violence (most of it, at any rate) has served as a stabilizing force and has girded our political equilibrium. For most of our history, it’s been a happy marriage, violence and stability, though the Civil War was a particularly nasty trial separation, and even there the parties reconciled, more or less.

An additional irony is that little of the vast smorgasbord of domestic mayhem has been insurrectionary. Our violence has lacked the sort of anti-government cohesion that might have caused it to become a sustained political phenomenon. Rather it has been local and largely repressive. While most repressive acts of violence have been perpetrated by whites against blacks, plenty of whites have died defending blacks. White mobs frequently lynched and white-capped[34] white abolitionists. The same Protestant mobs that rioted against Irish-Catholic immigrants later joined forces with the Irish against immigrant Mexicans and Chinese.

Social violence has a strong “conservative bias” aimed at preserving the status quo against “abolitionists, Catholics, radicals, workers and labor organizers, Negroes, Orientals (sic). And other ethnic or racial or ideological minorities, and has been used ostensibly to protect the Americans, the Southern, the white Protestant, or simply the established middle-class way of life and morals.”[35] “In one way or another,” agrees historian Richard Maxwell Brown, “much of our nineteenth and twentieth century violence has represented the attempt of established Americans to preserve their favored position in the social, economic, and political order.”[36] He’s not talking about elites alone. Brown’s conclusion is about the established order of things, which includes the vested interests at all levels of society. The status quo was the goal, not the enemy. Civil violence co-existed with institutional stability because it supports those institutions. Historically, riots suppressed social, cultural, and racial change. From the majority’s perspective, mob action smoothed out society’s rough edges by containing challenges to the status quo. For example, violence, especially in the form of lynch mobs, played a central role in maintaining African Americans as ignorant, impoverished laborers, precisely where the white majority wanted them. White mobs destroyed with absolute impunity prosperous black businesses and institutions such as churches, fraternal societies, communities, and on more than one occasion all-black towns. Historian Leon Litwack tells the story of a prosperous black Georgia farmer who upon driving his new car into the nearby town was forced by whites to watch helplessly as they poured gas over the car and incinerated it. That act and the mocking warning that accompanied it reinforced the racial hierarchy: “From now on you niggers walk into town or use that old mule if you want to stay in this city.”[37] The history of Jim Crow in the South is loaded with accounts of prosperous blacks with nice homes or competitive businesses losing one or even both, and often their lives. The hatred and stupidity of the white world would be pathetic if its racism wasn’t so downright mean.

Maybe so. But far more often violence has been employed to maintain the social fabric. One has but to look back to history’s violent counterpoint to see the weakness in this blame-it-on-the-60s meme. One of the most violent peacetime decades in American history was the 1890s. Actually, the entire “peacetime” period from 1865 qualifies. But the tumultuous decade that was more red than mauve stands out.[38] It was filled with riots, lynchings, vigilantism, gang wars, nativist harassment of immigrants of differing religions and cultures, and of course the final suppression of the Plains Indians.

Where were the counterculture and its “decadent” values in all of this? The answer of course is that in many ways the counterculture would develop partially in response to these sorts of things (plus, excessive materialism and the existential dilemma of being the first generation faced with the possibility of being the last generation. But, never mind.) In the Gilded Age, violence was often a vehicle for stability. And it was pretty damned effective. Those riots, lynchings, white-cappings and the like were utterly successful in preventing the assimilation into society of substantial portions of the population, both foreign and native-born. This was the age of Jim Crow. These events, and there were hundreds leaking into the thousands, were treated as local issues and generally ignored. Or, when a blind eye wasn’t possible—the 1898 Wilmington, North Carolina, coup d’etat that overthrew the legitimately elected, biracial regime in favor of a white one, for example — the events were cursorily investigated and then ignored. Social violence supported traditional values, in this case white supremacy, in the face of rapid and often incomprehensible change. Traditional values, mind you, are whatever the populace says they are. The local populace almost always sanctioned this violence as being crucial to maintaining social stability. The legality of their actions was of secondary importance. They argued they had no choice in the matter. Their backs were to the wall. Sounds odd, doesn’t it, lawlessness as an agent of stability? Sounds like moral relativism, perhaps. Nevertheless, outsiders and undesirables were contained or excluded, and local society remained politically and culturally stable—and violent.

But first things first. What do we mean by ‘violence’?

[1]Moynihan quoted in Barbara Ehrenreich, “The Warrior Culture,” The Snarling Citizen: Essays, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), 206 – 209. Moynihan quoted on 208.

[2] Lawrence M. Friedman, Crime and Punishment in American History, (Basic Books, 1993), 453. The term ‘peaceable kingdoms’ itself rests upon the notion of enforced homogeneity and is therefore ironic. See, Michael Zuckerman, Peaceable Kingdoms: New England Towns in the Eighteenth Century, (W.W. Norton, 1978) and Kenneth A. Lockridge, A New England Town: The First Hundred Years, (W. W. Norton, 1985).

[3] Quoted in Michael Feldberg, The Turbulent Era, Riot and Discord in Jacksonian America, (Oxford University Press, 1980), 60. The Know-Nothing candidate was elected mayor. The Democrats won the presidency.

[4] Adams quoted in Irwin Winkler, Gun Fight: The Battle over Gun Control, (W.W. Norton, 2011), 161–162. James Truslow Adams is not related to the political Adams family.

[5] Joseph S. Himes, “Violence and Social Conflict,” in Conflict & Conflict Management, (University of Georgia Press, 2008), 101.

[6] David Herbert Donald, Lincoln, (Simon & Schuster, 1995), 80-83.

[7] Paul Taylor, “The American Beginning: The Dark Side of Crèvecoeur’s ‘Letters from an American Farmer’,” The New Republic, July 18, 2013.

[8] Richard Maxwell Brown, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism, (Oxford University Press, 1975), 7.

[9] Brown, 41-42. Undoubtedly, he would have added the 1990s had the book not already been published.

[10] As an historic era, “the 60s” is often dated from 1960 to as late as 1975. I personally favor February 1, 1960 (the start of the Greensboro sit-ins) to August 9, 1974 (President Richard Nixon’s resignation, but it could just as easily range from JFK’s election to the fall of Saigon).

[11] William E. Leuchtenberg, A Troubled Feast: America since 1945, (Little, Brown, 1973), 174.

[12] The FBI considers four deaths the minimum number for mass murder (excluding the perpetrator). http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/serial-murder/serial-murder-1-two.

[13] There were over 500 riots between 1963 and 1970. Richard Maxwell Brown, “Overview of Violence in the United States,” in Violence in America: an Encyclopedia, Ronald Gottesman, editor, (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1999), 5.

[14] For a compilation of mass murders, see Mother Jones, “Guide to Mass Murders,” http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/07/mass-shootings-map. VOX maintains an excellent tracker of mass shootings since Sandy Hook: http://www.vox.com/a/mass-shootings-sandy-hook. Mass Shooting Tracker is a crowd-sourced shooting tracker. http://shootingtracker.com/wiki/Mass_Shootings_in_2015. There is a difference between mass murder and mass shooting. The instrument of death in mass murder varies.

[15] This sort of event was not altogether uncommon over the preceding 150 years. See James R. McGovern, Anatomy of a Lynching, (LSU Press, 1986).

[16] Hugh Davis Graham, “The Paradox of American Violence,” in Graham and Gurr, eds., Violence in America: Historical & Comparative Perspectives, (Sage, 1979), 479.

[17] Richard Slotkin, The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1800—1890, (University of Oklahoma Press, 1998), 62. The genocide of Native Americans was not the result of conscious policy or programs. It was more inadvertence and a largely heedless central government combined with localized action. The main causes of the genocide were disease and starvation: all the results of conquest.

[18] “The Weather Underground,” excerpt containing Dohrn quote http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YiIC8YwQVV8. For a compendium of these monstrous regimes and conquerors, see Matthew White, The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History’s 100 Worst Atrocities, (Norton, 2012); Richard Hofstadter, “Reflections on Violence in the United States,” American Violence: A Documentary History, Richard Hofstadter and Michael Wallace, editors, (Alfred A. Knopf, 1970), 6–7.

[19] “Quoted in David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, (Oxford University Press, 1980), 138.

[20] Richard Hofstadter, “Reflections,” 4, 10.

[21] Hofstadter, 3, 6; Richard E. Libman-Rubenstein, “Group Violence in America: Its Structure and Limitations,” in Graham and Gurr eds, Violence in America, 438.

[22] Richard Hofstadter, “Reflections,” 3, 6.

[23] See Jill Lepore, The Whites of their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle over American History, (Princeton University Press, 2010) or Ronald P. Formisano, The Tea Party: A Brief History, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

[24] Hofstadter, “Reflections,” 3.

[25] Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776—1787, (W. W. Norton, 1972), 319-320.

[26] In terms of the present population, the Revolution would have resulted in over 3 million deaths. Holger Hooch, Scars of Independence: America’s Violent Birth, (Crown, 2017), 21.

[27] One in forty or the equivalent of 7.5 million today would have been driven into exile. Houck, 21.

[28] Joel Poinsett quoted in David Grimsted, American Mobbing, 1828-1861: Toward Civil War, (Oxford University Press, 1998), 114.

[29] C. K. Chesterton, “What is America,” http://www.libertynet.org/edcivic/chestame.html

[30] Graham and Gurr, Violence in America, 479. Hofstadter, “Reflections on Violence in the United States,” 11.

[31] Timothy Snyder, Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, quoted in “Book World,” The Washington Post, September 6, 2015, B7.

[32] Hofstadter, Reflections, 11.

[33] Benjamin Ginsberg, “Why Violence Works,” http://chronicle.com/article/Why-Violence-works/140951/. Although Professor Ginsberg asserts violence as a primary instrument for change, his arguments about the central role of violence in the political, cultural, and economic affairs of a country could easily make the case for its centrality against the forces of change, that is, in maintaining the status quo. It is also important to remember that violence was essential to gaining independence and ending slavery, to cite two prominent examples.

[34] The term means ‘violently expelled’.

[35] Hofstadter, “Reflections,” 11.

[36] Brown, Strain of Violence, 5.

[37] Leon Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), 335.

[38] The pale purple color was the fashion rage of the decade.