Contrary to conventional wisdom, neither the excesses of the 1960s nor the proliferation of firearms is responsible for America’s violent ways. Rather, the causes are many and so deeply embedded in our history and culture they can be difficult to extract. But they amount to an odd combination of factors particular to the British North American colonies lying south of Canada, with active new factors and diminished older ones working hand in hand from the first boots on the East Coast to the latest mass murder on the six o’clock news.

There are as many theories about the causes of human violence as there are disciplines in the sciences and social sciences. People are violent, communities are violent, societies are violent, nations are violent. Violence is perhaps the main subtext of human history, violence with an extravagant helping of sex. But this tells us next to nothing about why some societies and cultures are violent and others are not. My goal is to explain why America has such a violent history. And why that history makes us such a violent country today.

Hugh Davis Graham offers four fundamental causes of violence: “(1) the federal, capitalistic structure; (2) racial and ethnic heterogeneity; (3) affluence; and (4) the American creed as reflective of our national character.” These dramatic charges demand some explanation lest they come off as 60s-era quasi-Marxist screed.[1] Here’s what Graham has in mind: With the economy in private hands, capitalists “have been endowed with great power to bestow rewards or mete out punishment” pretty much at will. The hierarchical nature of American federalism with a largely absent central government and even to some extent the state governments meant for most of our history that, until well after World War II, local landlords, factory owners, merchants, ranchers, bankers, in other words the capitalist establishment had far more control over their immediate societies than today. Such a traditionally American arrangement permitted and produced widespread violence. Whether to put down strikes or settle a range dispute, local power held local sway, regardless of the consequences.[2]

According to Graham, all racial, ethnic, religious, and class minorities compete with one another for crumbs from the WASP table. And that’s the fly in ointment; race has always been a big deal in the Americas, especially in the United States. Graham argues that whites have held on to the conquistadors’ share of the abundance at the expense of African Americans and other groups that have often contributed significantly that abundance. True enough, but it’s about far more than money and living standards. It’s about participation in the national shouting match. It’s about the consequences of the end of observer status. That is to say the rise of equality of opportunity. A country steeped in the Enlightenment twins of liberty and equality that simultaneously denies them to minorities and the lower classes, opens itself to trouble. When a certain confluence of circumstance and events takes place, frustration erupts into violence. And it’s not limited to minorities.

Thus, “given these self-reinforcing engines of aggression, and given ready access to such instruments of aggression as firearms, American society has been poorly equipped historically to cope with the violence it has generated.” The link between firearms and violence is problematic and will be discussed later. For now, it’s important to acknowledge the widely-shared belief that American violence is all about guns. This belief is mistaken. It is not about guns. Neither is it all about capitalism. Blaming capitalism is as misleading as blaming guns.[3]

So, why is America violent? Let’s start at the beginning.

Tabula Rasa

"Tierra!” came the excited cry from the crow's nest of the Santa Maria. “Tierra!” And what land it was: "... fair meadows and goodly, tall trees, with such fresh waters running through woods as I was almost ravished with the first sight thereof." Although this description came from an Englishmen describing the Chesapeake region to the north of Columbus's first landfall, it easily applies to the entirety of the Atlantic seaboard of the Americas, as they would come to be called. The land was breathtakingly rich and welcoming. The people, according to Columbus, were naked "... very well made, of very handsome bodies and very good faces." They were generous and peaceable. "They invite you to share anything they possess, and show as much love as if their hearts went with it. Yet, Columbus did not hesitate to add, "with fifty men they could all be subjugated and compelled to do anything one wishes." Why would he dare say such a thing? One Spanish soldier, possibly under Hernan Cortes, told it all, "We came here to serve God and the King, and also to get rich." That is precisely what happened. When Cortes showed up in the Aztec area of central Mexico with his 600 men, he conquered his friendly hosts with a thorough-going violence that would serve as a model for future generations.

Only the Spanish had the temerity to call themselves Conquistadors when the word described perfectly the outlook of all the original European settlers of this hemisphere, whether the Portuguese in Brazil, the Spanish in Mexico, the Dutch in New Amsterdam (New York), the French in the Mississippi River Valley or Haiti, or the English along the Atlantic seaboard, many of whom called themselves Adventurers. For Europeans the Americas were lands to be conquered. Whether it was for gold, God or national glory, the wilderness and the indigenous peoples were opportunities to be exploited. To the people who settled here, the New World was more than a virgin land offering the promise of a better life. The New World was an empty slate, ready to be molded in any way the European colonists and their African slaves could shape it. Only the vast wilderness and the native people offered any pre-existing structure. The Indians for the most part were swept aside by disease and conquest. In fact, the unformed nature of civilized life in the New World, the absence of governmental and institutional structure actually encouraged ruthless violence.

The unstructured nature of life in the wilderness allowed many colonists, the Irish and Scots from various borderlands in Great Britain, for example, to maintain many aspects of their culture. These borderlanders from northern England, Scotland and transplanted Irish, made up the last waves of British migration (1717-1775). Collectively, they were disrespectful of hierarchy and suspicious of authority unless they could control it, and once on the frontier leavened by conditions of near-constant warfare. The Scots-Irish were known at home for being sexually freer, ruggedly independent, and violent. Settling in the backcountry, from western Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia down through the Carolinas and south, they established clan-based communities long on blood-ties, clan feuds, sexual promiscuity, (one minister claimed 94% of his brides the previous year had been pregnant), rough and tumble fighting and other aspects of their culture. Settlers in one area of the Virginia backcountry named two streams Tickle Cunt Branch and Fucking Creek until the horrified Cavaliers that dominated the colony re-named them.[4]

The absence of pre-existing governmental infrastructure and effective law enforcement meant that frontiersmen often felt compelled to take matters into their own hands and settle disputes or matters of custom and social stability in any way they saw fit, or from their point of view, as necessity dictated. Only a minority of individual were inclined to stop the actions that colonists justified as necessary for survival. They viewed the primeval forests of North America inhospitable wilderness that would, under proper circumstances, yield vast riches. Superior force enabled them to turn the wilderness into a source of food and shelter, and to conquer the native peoples.

When Chief Opechancanough had enough of the land-hungry, food-stealing ways of the Jamestown colonists, he attacked their settlements in 1622, killing 347 of them and again in 1644. The colonists reacted with such ferocity that the Indian population in that area was decimated and it never again challenged the English conquest. This was not an isolated event. Conditions were so raw and tenuous in Virginia that Captain John Smith wrote in his diary of one man who murdered his wife and "had eaten part of her before it was known; for which he was executed. Now, whether she was better roasted, broiled, or carbonadoed, I know not, but such a dish as powdered [salted] wife I never heard of." To prevent such things from happening again, he issued his famous dictum, "he that will not work shall not eat," threatening forceful expulsion or execution of anyone who disobeyed. As the years passed the continued absence of institutional structure on the frontier such as law enforcement, courts, judges or police officers, and the distinctly slow response of colonial governments in sending militia from the coast, meant frontiersmen originated their own agencies of 'law enforcement' outside legal bounds. Living in isolation, armed to the teeth—a necessity at the time—and beholden to no one but Mother Nature, frontier settlers developed their own law and order. From this grew a distinctly American form of group (or social or collective) violence known as vigilantism, which was organized, extra-legal (or extra-judicial) action designed to uphold law, mores, and tradition: the local way of doing things.

Frontier/the Wild West

Local autonomy played a particularly important role along the frontier where the social order was fluid and fickle, and the “state is weak and or its rationalizing minions held in contempt.” It is perhaps for this reason more than other that the frontier looms large as an explanation for violence. “… In the rough life of the border there is scant recognition for law as law,” wrote James Truslow Adams, “The frontiersman not only has to enforce his own law, but he elects what laws he shall enforce and what he shall cease to observe.” Frederick Jackson Turner, the historian who in 1893 made his enduring observation that the frontier had a democratizing effect on society, described the frontier as the “’meeting point between savagery and civilization,’ where the ‘forces dominating American character’ can be found.” The frontier strips this new man, this American, of his “’garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin.’” This frontier may have made him anti-social but necessity also brought out his rugged individualism and his love of the unfettered life. Commenting on Turner, David M. Potter argued that the abundance of free land, when combined with “a temporary lowering of civilized standards” and weak or absent institutions such as churches and schools, allowed local residents are fairly free to use whatever means are at hand to hold on to what they’ve got. Thus, the frontier became an incubator for violence.[5]

As Edward Ayers observed, “Our national mythology assumes violence to be a natural outgrowth of the frontier.” Such reasoning was a matter of common sense, he argued, tellingly adding this: “In other English colonies such as Canada and Australia frontier challenges to those similar to the United States did not breed notoriously high levels of violence among settlers.” One of the enduring paradoxes of American violence is the centrality of the Myth of the Frontier, “our oldest and most characteristic myth, expressed in a body of literature, folklore, ritual, historiography, and polemics produced over three centuries,” according to Richard Slotkin, who has written extensively about the mythic role of the frontier in the development of the American character. Slotkin concludes that “Violence is central to both the historical development of the Frontier and its mythic representation.”[6]

So, we’re talking about both heroic myth and gruesome reality. Both of which are predicated upon the free use of violence. The mythic representation described an America in which people relied upon violence to suppress savage enemies that perceived or real, foreign or domestic. Violence enabled Americans to survive and prosper. The frontier required an on-going process of “regeneration through violence,” to use Slotkin’s insightful phrase. First, through territorial expansion through conquest and removal of the native peoples, accompanied by the defeat of a hostile wilderness. Then, after almost two centuries, defeat of the oppressive mother country led to re-birth as an independent republic. Later, violence was essential in maintaining a homogeneous society by suppressing various radical foreign or foreign-seeming elements from society after absorbing those useful elements and extirpating the rest.

Even today the frontier mystique pulls heavily at the American psyche. The 2015 film The Revenant is about the regeneration of a Wyoming frontiersman in the 1820s through violence and persistence. In the end he triumphs and extracts revenge. The frontier provided a hot house for “fatal flaws within the American culture: a brooding and pervasive sense of grievance and displaced frustration, an undue affection for guns, and a pessimistic evaluation of human nature that that automatically assume violence to be the inevitable—if unfortunate—recourse in the face of intractable problems.” Above all was the pressing weight of a man’s honor fortified with plenty of whiskey that insisted upon fight over flight, action over reason.[7]

Theodore Roosevelt later popularized this rugged individualism in his book The Winning of the West, which glorified self-help justice whether for personal or societal reasons. TR considered vigilante justice a critical aspect of Christian Americanism precisely because it was predicated upon self-sufficiency. James Truslow Adams added to TR’s notions in the 1920s by claiming lawlessness to be “one of the most distinctive American traits,” and thus provided the roots of “America’s propensity for violence,” as Irwin Winkler puts it, where a man carried the law on his hip. [8]

Adams was one of “generations of Americans [who had] grown up accepting the idea that the frontier during the closing decades of the nineteenth century represented country at its most adventurous as well as is most violent,” as one historian wrote, where, according to famed western historian Ray Allen Billington, “mobs of mounted cowboys ‘took over’ by day, their six-shooters roaring while respectable citizens cowered behind locked doors.” Popular imagination is filled with images of the lone gunman: Shane astride his horse riding into town to settle the bad guys’ hash. Which he does violently but with laconic charm before climbing back onto his horse and sauntering off into the brilliant sunset.

As if we needed proof of their impact, here it is. At the peak of his power and influence, Henry Kissinger, a Jewish refugee from Nazism, likened himself to a lone gunman riding into a dusty western town to root out the bad guys. In his case, the towns and bad guys lived in the Middle East. This is the universal American and a good indication of why cowboy politicians still resonate so well among Americans—except those on the sophisticated East Coast and Indian reservations.

We largely hold violence in defense of one’s honor as a frontier phenomenon, perhaps because the strong, silent, and righteous frontiersman possesses such attractive qualities. The cult of the anti-hero embodied in such romanticized figures as Jesse James, Billy the Kid, Wild Bill Hickok and Wyatt Earp. And the less-well known part-Cherokee horse thief, train robber, and murderer Henry Starr (distantly related to Belle Starr’s husband), who robbed in part as payback for the extermination of American Indians. Texas outlaw turned lawman, King Fisher had a somewhat different and perhaps more accurate take on the western gunman: "Fair play is a jewel. But I don't care for jewelry." Fisher killed twenty-six men before he met a violent fate: thirteen gunshot wounds during the so-called Vaudeville Theater Ambush in San Antonio in 1884. The road leading to his gang’s hideout was supposed to have been posted with a sign saying, “This is King Fisher’s road. Take the other one.” Henry Starr was killed trying to rob a bank in Arkansas in 1921.

Henry Starr King Fisher

Here’s Wikipedia’s list of Wild West gunfights:

• Bellevue War, April 1, 1840, Bellevue, Iowa

• Wild Bill Hickok-Davis Tutt shootout, July 21, 1865, Springfield, Missouri

• Gunfight at Hide Park, August 19, 1871, Newton, Kansas

• Going Snake Massacre, April 15, 1872, Tahlequah, Indian Territory

• Battle of Blazer's Mill, April 4, 1878, Mescalero, New Mexico

• Battle of Lincoln, July 15 through July 19, 1878, Lincoln, New Mexico

• Long Branch Saloon Gunfight, April 5, 1879, Dodge City, Kansas

• Variety Hall Shootout, January 22, 1880, Las Vegas, New Mexico

• Four Dead in Five Seconds Gunfight, April 14, 1881, El Paso, Texas

• Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, October 26, 1881, Tombstone, Arizona

• Trinidad Gunfight, April 16, 1882, Trinidad, Colorado

• Vaudeville Theater Ambush, March 11, 1884, San Antonio, Texas

• Hunnewell, Kansas Gunfight, October 5, 1884, Hunnewell, Kansas

• Frisco Shootout, Elfego Baca December 1, 1884, Reserve, New Mexico

• Tascosa Gunfight, March 21, 1886, Tascosa, Texas

• Luke Short-Jim Courtright Gunfight, February 8, 1887, Fort Worth, Texas

• Owens-Blevins Shootout, September 1887, Holbrook, Arizona

• Battle of Cimarron, January 12, 1889, Cimarron, Kansas

• Battle of Coffeyville, October 5, 1892, Coffeyville, Kansas

• Battle of Ingalls, September 1, 1893, Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory

• Shootout on Juneau Wharf, July 8, 1898, Skagway, Alaska

• Hot Springs Gunfight, March 16, 1899, Hot Springs, Arkansas

• Moab Shootout, May 26, 1900, Moab, Utah

• Battleground Gunfight, October 8, 1901, Fort Apache Indian Reservation, Arizona

• Gunfight at Spokogee, September 22, 1902, Dustin, Oklahoma

• Canyon Diablo Shootout, April 8, 1905, Canyon Diablo, Arizona

• Shootout in Benson, February 27, 1907, Benson, Arizona

• Naco Gunfight, April 5, 1908, Naco, Sonora

• Shootout at Sonoratown, May 15, 1911, Sonoratown, Arizona

• Gleeson Gunfight, March 5, 1917, Gleeson, Arizona

• Power's Cabin Shootout, February 10, 1918, Galiuro Mountains, Arizona[9]

Western “badmen” were described by historian Roger McGrath as “proud, confident, and recklessly brave individuals who were always ready to do battle and to do battle in earnest.”[10] Here is one largely unknown All-American badman.

Captain Jonathan Davis was on a mining expedition in California in 1854 when a gang of cutthroats bushwhacked him and his two companions. Both companions were taken out with the first volley. Davis, who was armed to the teeth and then some, killed eleven of the fourteen men, “seven with hot lead and four with cold steel.” Davis’s hat and clothes were riddled with something like eighteen bullet holes; his body suffered two minor flesh wounds.[11]

Yet, all this is extremely misleading.

First of all, most everyone associates the frontier, the West and the Wild West as one and the same. The frontier was a continually moving political, economic and cultural condition. The West was and is too vast to characterize, and the “Wild West” was a varying time period in parts of that vastness. Within the time and place of the Wild West, “the Mormon religious colony of Orderville, Utah, and the mining town of Bodie, California, were contemporaneous American frontier settlements, but … might as well have been on different planets.” The differences in social structure, as David Courtwright points out, were as vast as the territory.[12]

More important, “murder was not a daily, weekly, or even monthly occurrence in most small towns or farming, ranching, or mining communities.” Take Dodge City, Kansas, for example. Between 1875 and 1885, “0.165 percent of the population was murdered each year—between a fifth and a tenth of a percent.” [13] Statistically ridiculous—until one realizes that the populations of these Wild West towns were tiny compared to the metropolitan areas of the day that had far more homicides. In terms of sheer numbers, most collective and criminal violence occurred well away from the frontier, even the southern frontier in the crowded, impoverished, dirty and diverse cities east of the Mississippi, especially the burgeoning metropolises along the Eastern Seaboard. On the other hand, the West was often proportionally more violent. So popular perception, though influenced by dime novels and later movies and TV, was not completely off the mark.

The cult of the rugged individual has served us well in many ways, but it has also glamorized violent self-assertion in ways that have made the lone gunman of the Old West into the quintessential American. It shows just how dependent we are on "rough and tumble" images for a sense of our national self. The cowboy remains the quintessential and mythic American, when in terms of what was actually happening at the time, it should have been the small businessman.

Which image was more typical of the day?

or

The “Wild West” or more precisely, the Gilded Age frontier, played an important role in America’s violent ethos not because it was violent itself. But because it projected mighty images—often misleading images—of violence, honor, manhood—what it meant to be American. The West was not nearly as violent as its popular image. For example, Dodge City had a grand total of fifteen homicides between 1877 and 1886. True, fifteen actually represents a high rate, even if the overall numbers are low when compared to the big cities along the East Coast and the rural South. During Tombstone, Arizona’s single most violent year, 1881, five people were killed; three of those were in the legendary gunfight near the OK Corral. Deadwood, Colorado’s deadliest year had a body count of four. Not only that, “crime generally was rare in frontier towns,” and least of all were bank robberies. Banks were just too well fortified. One historian claimed in 1974 (and somewhat dubiously) that the West was “a far more civilized, more peaceful and safer place than American society is today.”[14]

Winkler’s survey of the historical record reveals a reality at serious odds with popular imagination. By far and away the most violent places in America during the Wild West days were American cities, particularly those along the eastern seaboard.[15] America’s major cities witnessed 1,266 homicides and murders in 1881, the year of the Gunfight at the OK Corral that resulted in three deaths. That number spiked to 4,290 in 1890 and 7,840 eight years later.[16] By contrast, homicides were rare in the West. During its cow town heyday, Dodge City averaged 1.5 homicides a year, fifteen total between 1877 and 1886. Tombstone’s most violent year came in 1881, when five men were killed, three of them in the OK Corral shootout. At the time Tombstone, Arizona, had restrictive gun control ordinances, which occasioned the famous Earp—Clanton firefight. “Throw up your hands, we’re here to disarm you.” Ike Clanton had been stumbling around town drunk with a pistol in one hand and a rifle in the other in violation of the gun control laws.[17]

Some of the early gun control laws appeared in the Wild West. Montana Territory banned in 1887 all deadly weapons, including sling-shots and brass knucks, in its towns and cities. Oklahoma made it unlawful “for any person in the territory of Oklahoma to carry concealed on or about his person, saddles, or saddle bags, any pistol, revolver, bowie knife, dirk, dagger, slung-shot, sword cane, spear, metal knuckles, or any kind of knife or instrument manufactured or sold for the purpose of defense.” Sounds like Oklahoma had a problem with violence not just with guns. What was true in these and other territories was true in most states as well.[18]

The point I’m making here is not about gun control, much of which is useless anyhow, it’s about the level of gunplay in the West. Guns didn’t make the West wild and wooly because the West wasn’t all that lawless and uncultured, at least not in the way of popular legend. In actual fact there was less gunplay and macho violence in Abilene or Kansas City than in Boston or New York City or Chicago; dozens compared to thousands. Between 1870 and 1885 there were forty-five murders in the cow towns of Abilene, Dodge City, Wichita, Caldwell and Ellsworth. During cattle drive season, which brought a heavy influx of “young, single, intemperate, and armed” cowboys, Abilene and Dodge City averaged 1.5 killings.[19] Two exceptionally violent mining towns along the California-Nevada border in the Sierra Nevadas were indeed sites of specular violence. Bodie, California, had thirty-one killings while Aurora, Nevada, sixteen or seventeen. The homicide rates in Boston and Philadelphia, for example, were considerably lower. Philadelphis,, for example, had a homicide rate of 3.7 from 1874 – 1880.[20]But the body count was far higher. Boom-time populations of about 5,000, meant those rates were sky-high, and in that sense these towns were arguably more violent in terms of murders per 100,000. Still, “there simply is no justification,” concluded Historian Roger McGrath, “for blaming contemporary American violence and lawlessness on a frontier heritage. The time is long past for Americans to stop excusing the violence in society by trotting out that old whipping boy, the frontier.”[21] Both Bodie and Aurora have been ghost towns since early in the 20th century.

Brawls, fights, lynch mobs, riots, racial bombings and the like would have taken place with or without the gun that tamed the West on everyman’s hip and a Winchester .30 across his saddle. Besides, the hyper-American face-to-face shoot-out in the streets, or “walk-down,” never happened, not even once. Few men no matter how drunk at the time would be so stupid as to stand out in the open and try to draw his sidearm, which he probably wasn’t carrying in the first place, beat his opponent to the draw and hit him standing even a reasonable distance away. The revolver had so much kick to it that there would be little hope of hitting his man with a second or third shot, unless he used two hands to hold the pistol—and there goes your legendary walk-down and quick draw shootout. “Nowhere in the Wild West, not ever, did two cowboys or anyone else stand in the middle of a street, revolvers strapped to their sides, and challenge each other to a fatal ‘quick draw’ contest.”[22]

Here’s the closest thing to it. At 6pm on July 21, 1865 in the town square of Springfield, Missouri, James Butler Hickok confronted a gambling acquaintance named Davis Tutt. The day before Tutt had grabbed Wild Bill’s pocket watch from the poker table where Hickok was playing and vowed to hold it until Hickok settled a $35 debt, a debt the humiliated Hickok denied and Tutt duly announced was now $45. Hickok warned Tutt of the consequences if he wore the watch around town. Tutt made a fatal mistake. Later on, out in the town square, Hickok accosted Tutt, who was brandishing the watch. From a distance of seventy-five feet, Tutt drew his sidearm and fired. He missed high and wide. Wild Bill pulled one of his two pearl-handled .36 caliber Colt Navy model revolvers, steadied it across his left arm and shot Tutt once in the chest. “Boys, I’m killed,” sighed Tutt, whereupon he stumbled to the wooden sidewalk and fell down dead. Wild Bill turned his revolver on Tutt’s friends, daring one of them to take exception. Two days later Hickok was arrested for murder. He was acquitted in what the jury termed a “fair fight.” Later accounts back East lionized Wild Bill and set the tone for the western gunman operating at the bleeding edge of the law.

Proving that quick draw shoot-outs never occurred doesn’t undermine the importance of Old West violence. Even if the facts do not support the widely held belief that the West was extremely violent. “What is distinctively ‘American’ is not necessarily the amount of violence or kind of violence that characterizes our history,” writes Richard Slotkin, “but the mythic significance we have assigned to the kinds of violence we have actually experienced.”[23] Most of the violence in the West was invented or exaggerated, but most this era became the bedrock of our cultural heritage, and violence became the “quintessentially American” way to save a respectable society.

But …

Was the American frontier violent? Yes, indeed it was: at times and in places extremely so. But it depends upon time and place. When one limits the frontier to the “Old West,” the results vary. During its glory days, the murder rate was higher in the West than major urban centers, but far more murders took place east of the Mississippi in the burgeoning metropolitan areas and in the Deep South. And that’s even if you factor in the annihilation of the Plains Indians. Far more of them succumbed to European diseases than industrial lead, anyway. So, here’s the critical factor, the “frontier” meant Jamestown in 1605, Plymouth Rock in 1620, east central Virginia in 1676, central Pennsylvania in 1763, rural Massachusetts in 1787, and Appalachia in the early 1800s. The “Wild West” didn’t come along until the Gilded Age—after the Civil War.

For example,

“By 1622 the … English had taken over a significant acreage of [Indian] hunting ground depriving them of essential resources. In a sudden attack on Jamestown, the Powhattans killed about a third of the English population. The Virginians retaliated in a ruthless war of attrition: they would allow local tribes to settle and plant their corn and then, just before the harvest, attack them killing as many as possible. Within three years they had avenged the Jamestown massacre many times over. Instead of founding their colony on the compassionate principles of the gospel, they had inaugurated a policy of elimination imposed by ruthless military force.”

The same was true of their Puritan brethren to the north, who “had no qualms about killing Indians … and justified their violence by a highly selective reading of the Bible.”[24]

What historian Sheldon Hackney wrote about violence along the southern frontier was often typical of colonial violence on any part of the frontier. "Violence was an integral part of the romantic, hedonistic, hell-of-fellow personality created by the absence of external restraint that is characteristic of a frontier." In colonial America violence was a far more pervasive formative factor than Puritanism.

After almost two centuries of conquest of the frontier along the eastern seaboard inland as far as the piedmont, the British colonialists rebelled for their independence. "Armed force, and nothing else, decided the outcome of the American Revolution," wrote historian John Shy. Without that violent victory, the Declaration of Independence would be merely forgotten words. As John Adams himself pointed out, the real revolution in the hearts and minds of would-be Americans to use violence to break their ties with England had been decided before that unknown individual fired "the Shot Heard Round the World." By necessity, the colonists were armed. Their lives often depended upon their ability with a long gun. Either for procuring food, defending the family or settling a dispute, firearms formed a vital link in the chain of being. Unlike other most other European colonists, the British in North America eventually used these arms to secure their liberty. British settlers were heavily armed well before the Revolution and as Americans remained so afterwards. This established an often overlooked link between violence and our liberty and independence as individuals and a nation. As early as the 1670's William Berkeley, the British governor of colonial Virginia, described his subjects as a people "Poore Endebted Discontented and Armed" and quarrelsome and difficult to govern for those reasons. Although it undermines our notion of colonial America as an Acadia of "peaceable kingdoms," our colonial history was fraught. From the very first settlement on, British colonists in North America were continuously at war. When they weren't fighting the French, the Spanish or the Indians, they were fighting each other over anything from political rights to territorial boundaries to fishing rights in the Chesapeake Bay. [25]

So, do the frontier heritage and the Wild West play a role in our violent culture even if the violence was exaggerated? I would say most definitely. It wasn’t the bad guys who were so violent. It was the good guys, the vigilantes and most especially the military that was busy removing the native peoples. In fact, the main source of violence in the West was the American military, or more fundamentally government policies towards the Plains Indians. European colonists, settlers and American western migrants more often than not negotiated with the native peoples, traded with them, purchased land from them to the tune of $800 million, and were not inclined to resort to violence. Co-operation was more common than conflict. With the American military the story was somewhat different. From 1865, under the command of General William Tecumseh Sherman, the U.S. Army waged a twenty-five year war against the Plains Indians. This violence was real. This violence was widespread. In the end of the Indian population was reduced by four fifths, in large part by famine, disease or warfare, courtesy of the military campaign. The gunmen were little more than a sideshow in Old West violence, albeit with extremely important consequences.[26]

The West, that vast triumphal stretch of America bounty east of the Sierra Nevadas and west of the Mississippi, was indeed home to gun battles, range wars, and genocidal slaughter. The frontier, on the other hand, started on the eastern seaboard and moved westward through the woodland interior to the Appalachians, then over them to the Mississippi, and across all the way to the Pacific, building myth as a nation and a people were built out of the wilderness. More important though, the frontier gave us the Code of the West, where a man was only as good as his word, and the meme of the Silent American, rugged individualist, independent, self-sufficient, peaceable and imperturbable until provoked. Despite most crime and much violence being urban, there is one other factor that comes into play when we talk about the influence of the frontier on American violence. "Covenants without swords are but words," according to Thomas Hobbes. In America this code of manly honor was actually first seen with eye-gouging in the backcountry, dueling in the ante-bellum South, and family feuds among borderlanders.

Honor

To those who knew him, Devil Anse Hatfield was a "simple, hospitable mountaineer, affectionate and home-loving." At the time of his rise to fame, he was a forty year old ex-Confederate captain and head of the large and rambunctious Hatfield clan of the Tug Fork area near Matewan, West Virginia. It was coal country. Just across the Big Sandy River in Kentucky lived his, the McCoys. His youngest, Cap Hatfield, could be congenial and friendly, but he could also be as cruel and vindictive as a bobcat. You would not have wanted to cross Devil Anse or any of his progeny. He was one tough son of a bitch. The McCoys made the mistake of crossing him. The Hatfield-McCoy family feud that started over star-crossed lovers and lingering Civil War animosities—the McCoys fought for the Union—became a matter of primal honor that lasted seventy years.

Personal honor rests on a person’s “inner conviction of self-worth,” “the claim of that self-assessment before the public” and the public’s reaction to this claim. “In other words honor is reputation.” Furthermore, “The opinion of others not only determined rank in society but also affected the way men and women thought.”[27] Or put another way, honor, or primal honor, can be defined as “a system of beliefs in which a man has exactly as much worth as others confer upon him.”[28] Honor is outwardly directed but it doesn’t have to be the same for all people and historically has varied according to region. In the American South and in the backcountry, honor, or the need to defend one’s honor, is most deeply bound up with violence in the form of retaliation or “satisfaction” for real or perceived insults. While the North valued personal restraint in the face of adversity. The Code of the West combines both. A man’s word is his bond and he is honor-bound to keep it even in the face of adversity. Once his good faith has been violated, however, a man becomes duty bound to defend his blemished name. In all cases, the sense of honor extends beyond the individual to the community or region.

Southern men were expected to settle their disputes themselves. “Never … sue anybody for slander or assault or battery,” Andrew Jackson’s mother told him, “Always settle them cases yourself.”[29] The South followed a code of honor where the North followed a code of dignity. As historian Edward Ayers wrote, “Northern culture celebrated 'dignity'—the conviction that each individual as birth possessed an intrinsic value at least theatrically equal to that of every other person.” Ayers adds, “Women, blacks and Irish immigrants were not treated as equals by native white men. Even those white men found their supposedly equal worth mocked by class distinctions.”[30] Manhood meant choosing to remain deaf to insults that would compel Southerners to action. Bertram Wyatt-Brown described northern sense of honor as “akin to respectability,” which he described as a modern version of honor. Victorian respectability had progressed beyond the older, stronger notion of honor that required violence. Still, “the ethic of honor was designed to prevent unjustified violence, unpredictability, and anarchy. Occasionally it led to that very nightmare.”[31]

The South was different. “…Honor was the catalyst necessary to ignite the South’s volatile mixture of slavery, scattered settlement, heavy drinking, and ubiquitous weaponry.”[32] “No man [is] safe from violence,” wrote one transplanted North Carolinian of Alabama, “Unless a weapon is conspicuously displayed on his person,” In his home state, “it is considered disreputable to carry a dirk or a pistol,” while “in Alabama, it is considered singularity and imprudence to be without one.” Not that you necessarily needed knives or firearms. One man had “his thumb cut off … in consequence of a bite by Bob Hutchins at the races” for calling his wife and mother whores.[33] In early frontiers days, biting, eye gouging and the like were actually more common than shootings. Often, these affairs of honor were efforts among poor whites to prove they were not slaves, and thus worthy of respect. As Edward E. Baptist asserts, “Enslaved men were not allowed to defend their pride, their manhood, or anything else … Therefore, the best way to insult a white man was to treat him like a black man, as if he could not strike back, and the best way to disprove it was to strike back.” “Readiness-for-vengeance … had long define[d] manhood, not only for whites in the antebellum South, but throughout much of Western history.”[34]

David Courtwright’s striking book Violent Land lays the blame for violent defense of honor, for violence in general, largely on single, young men. The most violent individuals in the world are men between the ages of about fifteen and thirty-five. Whenever a society or community or region gets top-heavy with single young men, rates of violence soars. Courtwright emphasizes the role of personal honor in the scheme, along with racism, consumption of alcohol, religious intolerance, lack of familial socialization and prevalence of groups of single men, “especially if they are armed and loosely disciplined.” Courtwright emphasizes a strong three-way connection between gender, honor and violence. In African American communities, he also points out, the hostile atmosphere with weakened familial ties became a hothouse for even more violence, this time in an urban setting with young black men as the perpetrators, just as territorial, just as desperate and hard-nosed, but drugs rather than gold or cattle as the object of desire. “America,” militant Black Powerist leader H. Rap Brown, “is a country that makes you want things, but doesn’t give you the means to get those things.”[35]

“The violent defense of masculine honor was most common in the South and along the frontier, where it characterized the behavior of both aboriginal and immigrant inhabitants.”[36] Though honor violence may have started there, it wasn’t limited to the backcountry or to the slave South. Whether they were backcountry Irish peasants or upcountry gentlemen, they eschewed the often non-existent courts in favor of personal violence. Their methods were mimicked in the 20th Century by organized crime from the Irish and Jewish immigrants and the Sicilian Mafia, to the Crips and the Bloods. All have embraced a slogan from the American Revolution—Don't Tread on Me. We have two folk heroes that indicate this. One is well established, the other a folk hero in the making. “Devil Anse is legend. Monster Kody Scott is legendary. You didn't disrespect Devil Anse unless you were someone like former L.A. gang member, Monster Kody Scott a Crip O.G. (Original Gansta) who had taken down more than twenty people. That's over fifteen more than Devil Anse admitted to. "Bangin' ain't no part-time thang, it's full-time, it's a career. It's bein' down when ain't nobody else down with you. It's gettin' caught and not tellin'. Killin' and not caring, and dying without fear. It's love for your set and hate for the enemy. You hear what I’m sayin’?"[37]

These men are removed by time, place and race. But the issue—blood honor settled by violence has remained constant. If Devil Anse Hatfield is not a common criminal, then neither is Monster Kody Scott. If Monster is a thug, then so is Devil Anse. Set or family it amounts to the same thing: place, kinship, and honor, especially male honor. Somewhere between the backcountry family feuds and the urban gang wars lies a defining aspect of the American character. It's part of us as surely as our love of individual liberty and our mistrust of government, as surely as we cherish the rule of law while praising rugged individualism. It helps to explain why D.H. Lawrence had a point when he wrote, "The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic and a killer." He might also have added, dedicated to family and exceedingly territorial. But the point really is: violence isn't a symptom of our problems. Violence is the problem. It comprises the other half—the unresolved half—of the American character.

“A man is not born to run away”

— Oliver Wendell Holmes

No Duty to Retreat

It goes by many names and takes several forms: Stand your Ground”/”True Man Doctrine”/”Castle Doctrine, ” the social and legal code known as "No Duty to Retreat” represents a complete reversal of English common law that holds one is obligated to retreat ‘to the wall’ before resorting to violent self-defense “Duty to Retreat” or “Seek Safety by Escape,” no duty to retreat is a basic ingredient H. Rap Brown’s famous dictum, and as such is far more implanted in our national psyche than it is in law, although that is changing as more states adopt Stand-Your-Ground laws and the Castle Doctrine.[38] A man, a real man, a true-grit American, the cowpoke with all the right stuff doesn’t back down. He stands his ground, stands tall against adversity. It’s a straightforward question of manly honor. In his famous majority opinion in Brown v. United States (1921), Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes made this clear: “... if a man reasonably believes that he is in immediate danger of death or grievous bodily harm from his assailant he may stand his ground and that if he kills him he has not exceeded the bounds of lawful self-defense.” To this Holmes added, “Detached reflection cannot be demanded in the presence of an uplifted knife.” Commenting on the Brown decision, Holmes famously remarked, “A man is not born to run away.” To that we can add this dictum supposedly given to a young Andrew Jackson by his mother: “The law affords no remedy that can satisfy the feelings of a man.”[39]

To retreat is unmanly. Just ask the otherwise milquetoast subway vigilante, Bernard Goetz, who riding the subway in 1984 refused to back down to subway thieves, pulled his hand-gun and started shooting to demonstrate the point. Or the latest self-styled redeemer of society, George Zimmerman, whom the court ruled was simply standing his ground. In both cases the ethic of honor was more important than the instrument of that assertion. The historical consequences of no-duty-to-retreat as a vital aspect of honor are there for all to observe. It suffuses the very concept of be an American. No man is obligated to back down from a threat to himself or his family. Unlike most European countries, to which the majority of American trace its origin, he is not obligated to retreat from violence until his back is against the wall, and there is no alternative but to fight back by any means necessary. He is obligated to stand and fight. The racial consequences of this have been especially profound.

“For too long, we’ve been blind to the unique mayhem that gun violence inflicts upon this nation.

— Barack Obama, eulogy, Charleston, SC, 6/26/15

Guns

Have we really been blind to the “unique mayhem” caused by gun violence? We’re almost as fixated on guns as we are on race, both hot topics in the national colloquy about the nature of our country. Guns are more prevalent than ever. In significant ways gun control is looser than ever. Almost every state allows people to carry a concealed handgun; more and more allow people to go abut their daily live with a gun strapped to their hip. Everyone knows we’ve drifted into an era of mass shootings by lone gunmen, and we’ve been there for several decades, even as overall violence continues to decline. [40]

Long guns, shotguns, pistols, revolvers, semi-automatics, automatics, guns come in many varieties and vary widely in stopping power. More important, unlike a hammer or a screwdriver, a gun is a tool that is designed to kill, not install a new shelf in the bathroom. The very act of pulling the trigger initiates an act of terrific violence, a shaped charge, if you will, sending a projectile in one direction and designed to make a major impression on its target, more often than not actually the intended direction. Firearms are indeed tools, but they are tools that are inherently more violent than, say, rakes or shovels. So, maybe we can quit this notion that firearms are just another farm implement propped next to the tractor. We talk about the widespread ownership of guns as though violence hasn't been a constant throughout our history. The problem with American violence is not as simple as the prevalence of guns. Without guns we would still be violent.

The lamebrain argument that ‘Guns don’t kill people. People kill people’ ignores this inescapable fact: Yes, people kill people—with guns. And guess what? The people who people kill with guns more often than not are themselves. Of the 30,000 annual gun deaths, slightly more than half are suicides. Guns are just about the easiest way to pull it off. Speaking of pulling the trigger, only three percent of gun deaths are accidental, and few of them are by kids. So, guns laying-around the house unattended are hardly a problem. Guns are a handy way to end human life. But they don’t provide the motivation to do it. Maybe we ought to have something like depression-control laws. They might cut down on gun violence. Eliminating suicides would cut gun deaths in half. Through gang related violence, which itself is often related to drugs and you’ve accounted for another three fourths of the remaining half. Gun control advocates might well promote their cause as suicide prevention. Except that sounds more than a little lame, doesn’t it? Well, they could always advocate the legalization of drugs, which might reduce gang violent, as would anti-poverty programs, etc.[41]

No one should deny that guns are closely linked to inter-personal violence. But, could the discussion about that link be misplaced? Given the present state of affairs, it may seem rather eccentric to claim guns aren’t really the point, or at least not the main point. But it seems to me that the unending soliloquies on ‘gun violence’ ought to focus more on ‘violence’ and less on ‘guns.’ Guns don’t make people violent. They just enhance a violent person’s ability to be violent. Motivation is key is this discussion. Firearms facilitate violence. They don’t cause violence; they are force multipliers, if you will. The 340 million plus guns in possession of American citizens do not mean these individuals are going to use those guns to shoot at one another, at unsuspecting passers-bye, or even at themselves. A well-armed populace does not automatically mean a violent populace. Guns do not make people violent. They enable violent people. Do away with their guns’ they remain violent. America was a violent place well before the proliferation of firearms and the development of the so-called gun culture. Despite this, guns play a secondary if not a tertiary role in the violence woven into the fabric of society. The bottom line is this: If guns were the problem, there would not be a problem.

Pervasive, deep and often unpunished, most violence would have occurred even if most participants weren’t carrying guns. Because, in fact, they weren’t. And yet the mayhem they managed to commit was far more widespread and gruesome. Look at it this way: if all the guns suddenly disappeared from civilian hands, America would still be a violent country. Guns didn’t make us violent in the past and they don’t make us violent today. We have always been a violent people, even before we were a people. Even when they were English subjects, the people whose offspring became Americans were plenty violent. Americans and their forebears are unendingly inventive, and they were forever inventing ways to kill one another. In the case of rough and tumble, eye-gouging fights, guns actually eliminated that particularly barbaric kind of violence, if not the braggadocio that went with it.[42]

Gun control—self-control. You don’t need to carry a gun on your hip or in your purse when you go to the mall. Yes, in many if not most places, you have the right to do so. The Supreme Court said so (except, of course, around them). But should you exercise that right? How do you school self-control when violence and guns are offered as the solution to fear and anxiety? Confronted with oppression? Start blazing away. Confronted with crime? Start blazing away. Confronted with social disorder? Start blazing away. Confronted with terrorism? Start blazing away. Intruders in the night? Start blazing away.[43]

The ‘us versus them’ mentality that pervades our society supported by the Castle Doctrine and Stand-Your-Ground laws allow and justify violence that could be avoided. The simple fact about gun violence is this: George Zimmerman should have turned and run.

Immigration

February 14, 1929, St. Valentine's Day: "The first sweeps of the machine guns sprayed .45 slugs across the victims' lower backs and at the level of the upper shoulder, neck and head. Mat started to turn ... [and] buckshot blew the left side of his scull away. Four of the victims fell straight back to lie supine at right angles to the now pocked wall. Pete Gusenberg slumped into a chair ... with his chest over the back of it, body sideways on the seat. One machine gunner squatted and sprayed the line of bodies one last time, putting holes in the tops of heads, his misses ripping through upturned feet." The most famous of all the gangsters was Alphonse Capone, Scarface, who ordered the St. Valentine's Day Massacre of his rival Bugsy Moran's gang. He was born in 1899 in New York of Neapolitan immigrant parents and grew up in a lower class neighborhood inundated with violence. By age twelve he was a member of Johnny Torrio's James Street Boys. He got the scar at age eighteen beating up a woman, whose brother slashed him with a razor. Eventually following Johnny Torrio to Chicago, Capone took over the organization and through intimidation and raw violence rose to a position of power during the Roaring 20's. Though never a member of the Mafia because of his Neapolitan parentage (the American Mafia was Sicilian), he muscled into so much criminal territory in such a flamboyant way that his name became synonymous with organized crime.

Why has so much violence taken place in urban areas? The answer lies to a great extent in the cosmopolitan mixture of race and ethnicity. Race has been the preeminent cause of American civil disorder. Indeed, the harshest violence erupted from racial and ethnic conflict. As we’ve seen, white supremacy rested upon violence, both during slave time and well after. Whenever the white population felt even vaguely threatened by black revolt or peaceful progress toward equality, whites were likely to resort to violence, whether it was to punish a perceived criminal or to prevent black political participation or economic progress. This rule also applied to nativist reaction to Roman Catholic immigration in the East and Chinese railroad construction workers in the West. Ironically Protestants and Catholics joined forces when they felt threatened by the Chinese, as in Denver, Colorado in 1880 or Rock Springs riot in 1885, which was the worst case of anti-Chinese violence on record. Rampaging white miners slew twenty-eight Chinese workers.[44]

Rapid urbanization breeds rapid change. Change tends to shake established foundations, if not alter them entirely. Urbanization was a key factor in challenging the status of women, for example. Given that people are often inhospitable to change, especially those who think they have the most to lose, jobs, opportunity, status to a new group, change can lead those most directly affected straight to violence as a sure way to prevent or roll it back. Urban riots effectively contained many recent arrivals from blacks out of the South to Irish and southern Europeans off the boat to Mexicans across the border.

Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. blamed urban violence on “unhealthy urban growth, unrestricted immigration, the saloon, and the maladjusted Negro.”[45] Immigrant and domestic migration have made metropolitan centers the most violent locales within all regions in the country, as they continue to be. It’s an obvious fact that urbanization produces violence, everywhere, throughout history—even North America. At the same time European immigrants were moving into America, blacks had begun migrating from the fields of the South to the cities of the North. They crowded into inner city areas similar in nature, at first, to the areas occupied by the New Immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. Blacks faced racist violence in the cities and factory towns from competing workers. European immigrants became embroiled in the Labor Movement, which was the most violent of any industrial nation. Once outside the South, recent black arrivals in the industrializing cities found themselves still outside the law, again not by choice. Like some of their European counterparts, they began to settle disputes on their own. Irish, Italian and Jewish criminal organizations developed because established society failed to extend traditional benefits and protections to these non-traditional arrivals, which then fended for themselves, urbanizing our violent cult of honor. The three-day Chicago riot during the Red Summer of 1919 broke out when a black child swam onto the white portion of a segregated beach and was stoned to death by outraged whites. Twenty-four black homes were bombed: twenty-three blacks and fifteen whites died. Prohibition and the Great Depression produced violent folk heroes that harkened to the recent past of the Old West (1865–1890). These figures, most notably Al Capone, John Dillinger, Bonny and Clyde and Pretty Boy Floyd, helped continue the legacy of gang violence, which had begun to decline.

Migrants to the cities tended to be young men. When unemployment or reduced opportunities are added to their statistical predisposition for violence, this does not bode well for cities with stagnant or declining economies. Lowered revenues often if not always meant lowered educational opportunities and diminished social services. Education breeds hope. Young men without hope are more easily drawn into violence. Add racial and religious/ethnic differences to the lovely mix and you’ve got problems. Once people conclude that the possible benefits from violence exceed the potential costs, when, in other words, violence is worth the risk, you get criminal and anomic violence. Criminal violence is frightening enough. Anomic violence, wanton, seemingly mindless destruction of life and property in spats of “wilding” is the combustion of our waking nightmares. The black teenage “super-predator” emerged in early 1990s and frightened the bejesus out of white society. Which, one would have to concede, was more than half the point anyway, personal honor and manly respect being of prime importance to the American male, black, white, Indian, Hispanic, Asian or gay.

With our cities especially, our “extravagant diversity” is actually part of a larger, wider source of heterodoxy. Pluralism has put local restraint to the test repeatedly and with predictable results. Please note, culture clashes produce violence everywhere in the world and have done so throughout history. At present note the sixty year religious/cultural clash in Kashmir. Or the twenty year religious/nationalist clash in Sri Lanka between the Tamils and Sinhalese. Over the past few decades, this latter has produced some of the worst terrorist violence of the 20th century, and has not one damn thing to do with us. So, I'm not saying America is any different. That, unfortunately, is the point.

With its open doors and welcoming arms, America has drawn people of differing cultures, ethnicities, religious and values from all over the world on a scale unmatched ever. We called it a “melting pot” when it was anything but. Only the earliest settlers blended in the melting pot, minus African slaves. After that we became more of a tossed salad, tossed, that is, by hand grenades. Especially in our cities, that’s we’re the shoulders rub and worldviews clash. "No Dogs or Irish Allowed,"[46] "No Irish Need Apply." For the 1.2 million Irish immigrants arriving in the Promised Land these were unwelcome words that reflected English sentiments back in the British Isles. For Irishmen who had a difficult time finding work in the overcrowded cities, the coal fields of Western Pennsylvania became their avenue to the American Dream. The nativist coal operators treated them poorly, forcing them to work long hours at low pay under dangerous conditions. The Irish reacted to this treatment like other immigrant groups; they formed mutual aid societies for emotional and financial support. One of the largest and most mysterious was the Ancient Order of Hibernians, which the Irish brought with them to these shores.

A Harvard Math professor and troubadour by the name of Tom Lehrer once concocted some of the damnedest little political ditties of his era (1950s to mid-60s, after which history moved swiftly past his refreshingly innocent take.). Here is a stanza from his song “National Brotherhood Week” that illustrates the problem presented by pluralism.

Oh, the Protestants hate the Catholics

And the Catholics hate the Protestants,

And the Hindus hate the Moslems,

And everybody hates the Jews.

Plug in white - black, white - Indian, white - Mexican, black - Korean, Native born – Irish or any eastern or southern European ethnicity. We’re really dealing with race, religion and culture, pretty much in that order. I might add, though, that the positive side of America is that historic animosities such as British-French, Japanese-Korean, Japanese-Southeast Asian (actually, Japanese - any other Asian group) and so on mean not so much over here where Asians have been crowded into one amorphous demographic group, a rather small price to pay considering the alternatives.

"Abundance has influenced American life in many ways, but there is perhaps no respect in which this influence has been more profound than in the forming and strengthening of the American ideal and practice of equality."[47] These words by historian David M. Potter in his 1954 book People of Plenty seem revoltingly naive today when one considers the widespread poverty that was a hidden part of American life until Michael Harrington “re-discovered” it in 1962 in The Other America. During hard times pockets of poverty spread into regional poverty. People living there were in no way people of plenty. In the face of the ethos of prosperity and opportunity, which we commonly call the American Dream, many elements of society have at one time or another resorted to violence either to gain prosperity or to hold onto what prosperity they had. The melting pot has to a certain extent failed. Only immigrants from northwest Europe coalesced into a common culture. Many other cultures from South and East and Central Europe to Asia and Africa have remained to a degree isolated. America remains a society of fragmented cultures. Competition for pieces of the pie among people from within the mainstream has produced tensions that often erupted into violence born of blunted hopes. Members of any culture who feel stymied in their quest for material, cultural, and spiritual progress have often expressed their dissatisfaction through violence. Frustration aggression has led to some minority groups being used as scapegoats for the failures of others. It has led to lynchings, riots and whitecappings. On the other hand, the blunted efforts to share in America's considerable prosperity has led at other times to a revolution of rising expectations, as in the riots of the Long Hot Summers and more recently in the Rodney King Riot, which were more insurrections than riots. This trait has most often been attributed to southerners. But violence based upon material frustration has not been limited to them. It became an important aspect of the labor riots in the North and West and the urban racial problems that followed the Great Migration after 1910.

Race

In America race trumps everything. Race is far more influential in American violence than firearms or the Wild West. Or, the 60s. Race is one of most significant causative factors underlying American violence. Why? It’s this simple: Violence was necessary to maintain both slavery and maintain white supremacy that followed it. That’s 300 years or more of repression; a powerful and tough tradition to overcome. The slave-holding South had to rely on swift often brutal reaction against anything from a recalcitrant slave to runaways to uprisings. Otherwise, slaves would have overthrown the system and white-dominated society, and large swaths of American society including most of the slave South could well have disintegrated. Ironically, after slavery was brought to an end by the worst war in American history, fears of revolt or disruption by freedmen intensified. Jim Crow produced even more open violence than existed under slavery. For white society it was a matter of honor. For blacks a matter of survival.

Historically racism exacerbated already volatile situations by “inspiring and rationalizing interracial attacks” and undermining the stabilizing force of family and community through the exploitation of black women and the emasculation of black men, and by blocking interracial marriages, all of which promotes violence. In addition, racism also spawns violence by “impoverishing, isolating and socially marginalizing minority groups.”[48]

Race: Slavery

Slavery is inherently violent. It depends upon violence; it breeds violence. It is one of the most violence institutions ever created. No one—No One—ever voluntarily becomes a slave. People are forced into bondage against their will and kept there against their will—through violence or threat of violence. Violence lies at the core of slavery.[49] All slave-holding societies are violent societies. There are no exceptions. A slave society must be armed and vigilant and willing to use ruthless violence against its slaves or their allies upon a moment’s notice. Failure to do so is to invite rebellion. And even then vigilance might not be enough. Resistance in one form or another is the natural attitude of the enslaved. Often the only way to cope with resistance is through forced deportation, [50] the lash, branding, maiming, or death. The prospect of slave revolt was a fact of day-to-day life in a slave-holding society.

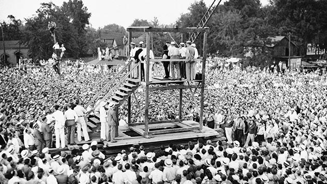

Calling for war on Christian white people, a Caribbean Obeahmen and Vodun (voodoo) priest transplanted from Haiti, organized the largest slave revolt in American history. The date was 1811, the place was St. John the Baptist Parish outside of New Orleans. Led by Charles Deslondes, a free mulatto from Haiti, close to 500 slaves armed themselves with a few firearms, and farm tools such as axes and machetes. Fired by the indignity of renewed oppression on the North American continent after having been taken by their fleeing masters from the successful Haitian slave revolt, they marched on New Orleans to conquer the city and hold it hostage for the abolition of slavery. A free black militia and federal soldiers led by General Wade Hampton met and defeated the untrained, loosely organized slave army after it had burned a few plantations and killed a handful of whites. In a murderous rage, vengeful and fearful whites killed sixteen rebel leaders and slaughtered sixth-three more blacks, cutting off their heads and mounting them on spikes along the road into New Orleans. As historian Eugene D. Genovese remarked, "The 'savages' had been beaten. Civilization had triumphed."[51]

Yet it was not slave revolts that made slavery one of the most important contributors to our violent heritage. Compared to other slave societies in the Americas, there were relatively few slave revolts in North America, while Central and South America existed in a continual state of slave revolt. Owing to enforced illiteracy and geographic isolation that left slaves with few places to escape to and the knowledge to get there, North America had but a handful of actual revolts and conspiracies. Far more important, it was the violence of the masters that added a strong layer of violence to the society. Slaves were acquired and kept by force. Slave drivers used it demonstrate their superior power and underscore the futility of resistance. Violent repression and retaliation was sanctioned in law and custom. “As early as the 1790s Thomas Jefferson observed that the unbridled authority wielded by slaveholders tended to breed impetuous behavior and shortness of temper, characteristics passed from generation of masters to the next.”[52]

In 1656 Maryland slave owner Symon Overzee owned a slave named Tony who showed his outrage at his enslavement by running away. His master used bloodhounds to capture him, and beat him severely afterwards. Once his wounds healed, Tony ran away again. Re-captured, he staged a sit-down strike, telling his master he refused to work as a slave. When a severe lashing failed to change Tony's mind, Symon Overzee hanged him by his wrists and poured hot lard over him. Three hours later Tony was dead. A year later, the colonial Maryland court decreed of Overzee, "The prisoner acquitted by Proclamation." In this way, the legal structure condoned and even encouraged capital crimes in order to maintain slavery. This helps illustrate why violence did not diminish as America progressed through the centuries up to 1865 when slavery ended. The rigors of the peculiar institution sanctioned the notion that when it came to maintaining slavery, no act of violence was a crime. All slave societies harbor a low threshold of violence in response to two factors: the need to hold the slaves in bondage, and the fear of (and a few actual) rebellions. Millions of restive slaves, who were in continual rebellion in one way or another, had to be controlled. For that reason, a fearful white society encouraged slave owners to operate largely outside the law. One runaway woman was re-captured, dragged back behind a horse by her owner and tied to a bedstead. Apparently still not satisfied, her owner attempted to cut off her breasts and followed that up by “ramming a hot iron poker down her throat.” As President Ulysses S. Grant commented dryly, "Slavery was an institution that required unusual guarantees for its security wherever it existed."[53]

As the decades passed in the slave South, the job of guaranteeing the security of the institution fell to private armies hired by slave owners. The slaves called them "pattyrollers" (patrollers), the unorganized militias that roamed the countryside guarding against insurrections and runaways. Thus, at the time other countries like Canada and Mexico were experiencing less social violence, areas of this country saw continuing and often expanding violence. The free states had markedly less criminal and social violence. Historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage commented, "Slavery also contributed to the weak legal institutions that increasingly distinguished the South from the rest of the nation." Largely because of the peculiar institution, white southerners, as W. J. Cash wrote in his seminal book The Mind of the South, had "an intense distrust of, and indeed, downright aversion to, any actual exercise of authority beyond the barest minimum essential to the existence of the social organism." Southern whites relied instead on their sense of honor and extra-legal violence to maintain racial, social and moral order.[54]

When they weren't lynching blacks and whites suspected of fomenting slave revolts, white mobs in the Old South often lynched white abolitionists to silence their anti-slavery views. The South developed a reliance upon group violence and the code duello of individual honor that took root in the late 18th century to maintain a sense of social decorum. In other areas of the country, law enforcement officials held responsibility for these functions. Not so in slave-holding areas. Because people of African descent, i.e., the slaves, were considered inferior and uncivilized, whites convinced themselves they were as free from moral culpability as they were from legal reprisal. For them it was an unquestioned right of survival.

We must also bear in mind that for most of its history in North America, “slavery was not a southern institution but a continental one,” as historian Ira Berlin underscores, “as much as home in the North as in the South, in New York and Philadelphia as fully as in Charleston or New Orleans.” And that institution, as Berlin has written so cogently about in recent years, was “the story of victimization, brutalization, and exclusion.”[55]

All of which lasted well beyond the 1865 ratification of the 13th Amendment that removed the Constitutional sanction of slavery.

Race: Segregation

Slavery may have died but racism reigned supreme. When slavery died, segregation replaced it. When the Civil War ended, racial violence did not diminish. In fact, it grew worse. Whites used violence to keep blacks from exercising their rights of citizenship guaranteed by the newly adopted 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments. No other country in this hemisphere experienced anything similar to Jim Crow. Throughout the world, only South Africa established the same type of racial system. There the white minority government enforced white supremacy rather than private citizens. In 1900 South Carolina Senator Pitchfork Ben Tillman said this from the floor of the United States Senate: “It was generally believed that nothing but bloodshed and a good deal of it could answer the purpose of redeeming the state from negro rule and carpetbag rule.” Referring to the Hamburg Massacre in Edgefield County in 1876, he added, “the purpose of our visit was to strike terror, and the next morning when the negroes who had fled to the swamp returned to the town the ghastly sight which met their gaze of seven dead negroes lying stark and stiff certainly had its effect ... The state of South Carolina has disenfranchised all of the colored race that it could under the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. We have done our level best, we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them, and we would have done it if we could, we took the government away. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it.”[56]

In Tillman's state using violence to achieve political ends—in this case maintaining (re-establishing in his view) white supremacy—was known as the Edgefield Policy. A contemporary of his, a former Confederate General named M.W. Gary, described it this way: “Every Democrat must feel bound to control the vote of at least one negro, by intimidation, purchase, keeping him away or as each individual may determine, how he may best accomplish it ... never threaten a man individually, [for] if he deserves to be threatened, the necessities of the time require that he should die.”[57]

At the same time in neighboring, racially “moderate” North Carolina, a prominent businessman and former Congressman Alfred Waddell made the following remark on the eve of the November 10, 1898 race riot/coup d’etat that would drive blacks from office and the city of Wilmington. “[N]igger lawyers are sassing white men in our courts; nigger root doctors are crowding white physicians out of business …We will not live under these intolerable conditions. No society can stand it. We intend to change it if we have to choke the current of the Cape Fear River with Negro carcasses.”[58] The riot that resulted offers perhaps the clearest example of how violence accompanied segregation. In spite of Jim Crow laws in the state, the black community in that thriving port city of 17,000 had managed through determination and cleverness to share in the general prosperity. By fusing with white Populists, they continued to elect black men to high local office and George H. White to the United States House of Representatives. The majority black population held a slight edge in number of offices. The white population found this intolerable. Blaming a nonexistent wave of interracial rape upon black equality, whites formed 'gun clubs' and staged a riot that really amounted to a coup d’état that drove all the black elected officials from office and forced some 2,100 black residents including professionals and skilled craftsmen in this 2/3 black populated city to flee for their lives. With as many as 100 blacks killed and dumped into the river, the Wilmington riot succeeded where the segregation ordinances had failed—the re-establishment of total white supremacy. A white officer called it “the quietest and safest riot I've ever seen.” Alfred Waddell appointed mayor by the now all-white city council. Two years later, white supremacy was cemented in a white supremacist landslide. Said Waddell: “You are Anglo-Saxons. You are armed and prepared and you will do your duty … Go to the polls tomorrow, and if you find the negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls and if he refuses, kill him, shoot him down in his tracks. We shall win tomorrow if we have to do it with guns.”[59]

Congressman White commented in 1901, “I cannot continue to live in North Carolina and be a man.” When he left office that year, White was the last black man elected from the South until Andrew Young won a congressional seat in Georgia in 1967. In Atlanta, Georgia, during the 1906 gubernatorial election, armed whites supported by the police marauded through middle class black neighborhoods, hanging men from lampposts and torching respectable homes as part of heightened anti-black furor that had been whipped up by race-baiting politicians. A bitter white population murdered and burned away the civil rights of black Americans.

The crushing weight of racial repression pressed relentlessly on black America. While the people were technically free and equal, the white South, or large portions of it, vowed to maintain white supremacy. Hence, segregation laws and brutalizing violence that became part of the legacy of the Civil War. During the latter years of the 19th century, a black person was lynched every two and half days. The day-to-day harassment was so pervasive that local ordinances required black men step off the sidewalk into the gutter whenever white women passed by. Black men especially were brought up on a racial etiquette that instructed them never to look a white person directly in the eye. The result of such a violation of the racial code could easily be a lynching, perhaps leading to a riot.

In 1921 whites burned the black business section of Tulsa, Oklahoma—the so-called Black Wall Street—rather than live with prosperous black people. The same thing happened to the black town of Rosewood, Florida, in 1923. Destroyed by resentful whites. As with the Wilmington Coup in 1898, whites would go to any length to prevent black equality. Lynch mobs often contained thousands of people, and lynchings were often announced in advance by local newspapers. Attendance was sometimes facilitated by special train service. Far fewer than one percent of all lynchers were ever apprehended despite the open, public nature of most lynchings, let alone brought to trial. White supremacy was synonymous with law and order. Imagine that sort of crime wave being broadcast on the nightly news. The public would conclude society was on the verge of collapse!

These practices stopped only after public opinion—regional and national—forced state law enforcement to put an end to it. The electronic media played a key role in this. Without radio and television, the Civil Rights Movement would not have succeeded to the extent it did when it did. Southern and many non-southern newspapers were ardent segregationists, as were most established white churches. Still, as during slave days whites could wreak violence on African Americans with relative impunity. This legacy remains a problem to this day, especially as exercised by police, as appointed representatives of society.